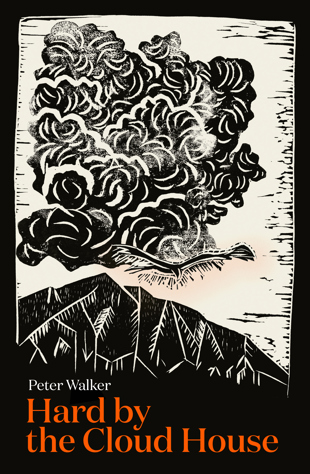

Ashleigh Young reviews Hard by the Cloud House by Peter Walker for Newsroom:

‘“Show us the bird,” I found myself muttering at times while reading Hard by the Cloud House by Peter Walker, a deeply thoughtful, often hilarious, at times rambling – but somehow delightfully so – search for the story of a big bird.

But not just any bird: the bird. This is Harpagornis moorei, Te Hōkioi, Haast’s eagle, the pouākai – dangerous, beautiful, doomed. The prehistoric eagle with feet and claws the size of a tiger’s, and a big head. Its body was about four times the size of a golden eagle, and by some Māori tales it had a habit of swooping down off mountaintops and carrying off men, women and children, as well as grabbing moa, in scenes I imagine to be the land equivalent of the battles between sperm whales and colossal squid. Like so many of the extinct, Harpagornis has been misjudged at times. With the discovery of a single huge claw in a bog in Glenmark, Canterbury in 1871, it was deemed the great apex predator of the Southern Alps. Not long after, it was dismissed as a disgusting flightless scavenger, “rustling from corpse to corpse for its next meal”. A part of me wishes our understanding of the bird had stopped here; the history of birdlife in Aotearoa is rich but it is missing a huge, dismal scavenger. Nearly a hundred years later, though, a caver in the Oparara Basin found a big wing bone shaped like a spoon, and after a scuffle with a museum and a new discovery at Sunrise Basin, the bird was once more crowned “a lion of the sky’” with a CAT scan of its skull in 2009 confirming, at last, its fearsomeness.

As Walker argues, so much of the eagle’s story is missing. The bird is a cloud of stories and names and allusions. Its bones have been picked up and looked at then thrown in the bog again; it has been “left out of the ecosystem of symbols”. After this realisation, we see Walker constantly on the move, hunting through libraries, walking with an old school friend through Tāwera, immersing himself in the 10th and 11th century literature of Baghdad, especially the Arabian Nights. As a narrator, Walker appears, disappears, appears again. Sometimes his book feels as though it has become the cloud itself. But this is surely the point: this bird’s story cannot be separated from the places and people, the science and mythology from which it arose; even a long, often moving sequence about Walker’s friendship with the artist Jim Viviaere, who accompanies Walker on a trip to Raiatea as press photographer – “You’re the photographer, remember?” “I despise photography” – gives momentum and meaning to his search, sending Walker to investigate the history of Taputapuatea.

Walker is very good at the business of having your heart quickened by discovery. Some moments are as small as Walker sitting in the British Library, reading a book about Honeycomb Hill in New Zealand and being startled awake by the description of a stream as “tea-brown”; or the suggestion in Māori legend that the great eagle flew with its head downturned as it swooped to attack. Sometimes there’s a boyishness about his excitement, as when he follows a theory that Harpagornis was connected with the Rukh who terrified Sindbad the sailor from Basra, or with China’s legendary bird, the huge and cloudy P’eng. But it is also a book about the obstacles to those heart-quickening moments, the difficulty of really knowing anything for sure, and the slipperiness of names: the “midge-dance of nomenclature over all the valleys and peaks”. That cloud, again.’

Read the rest of the review here.