6. The professional era

Gordon Harold Brown was born in Wellington in 1931 and trained

as an artist under Ted Lewis at Wellington Technical College. He

remembered two significant encounters from his teenage years

in the capital. One was with László Moholy-Nagy’s 1947 book

Vision in Motion, an introduction to the principles of the Bauhaus

and a blueprint for an education in and through art, which he came

across in Roy Parsons’ bookshop on Lambton Quay. The other was

seeing Colin McCahon’s 1948 painting Takaka Day and Night at

Helen Hitchings’ dealer gallery in a converted warehouse space

at 39 Bond Street.

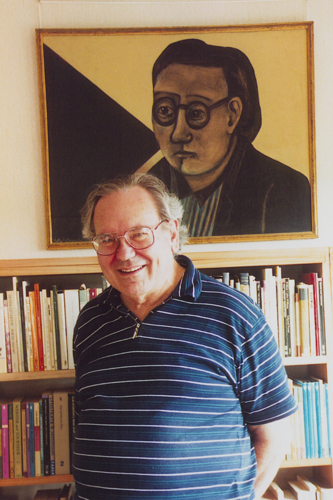

Brown, subsequently, as a first-year student at the Canterbury School of Art, met McCahon when he went around to his house in Christchurch with a letter of introduction from poet James K. Baxter. A Cubist-influenced painting was leaning up against the sofa, they began to talk about it, and so a life-long conversation began. McCahon’s 1968 portrait of Gordon Brown entered the Sarjeant’s collection in 2007.

Brown was an artist and a photographer as well as a librarian, art historian and curator and an exceptionally able administrator. He was always innovative in his approach. Of the curriculum at art school in the 1950s, with its focus upon still life, landscape and the drawing of plaster models of statues from antiquity, he remarked, ‘anything modern had to be done outside the classroom’. After graduating with a Diploma of Fine Arts in 1956 he trained as a librarian at the National Library School and, in 1960, joined the Alexander Turnbull Library. He was librarian at the Elam School of Fine Arts in Auckland and then research librarian, the first to hold that position, at Auckland Art Gallery after Peter Tomory left to take up a position at the newly formed art history department at the University of Auckland; Colin McCahon had gone across to Elam, where he would teach for the next seven years.

A prolific writer, Brown contributed 50 items to the first 50 issues of the quarterly journal Art in New Zealand. In 1969 he co-authored, with Hamish Keith, An Introduction to New Zealand Painting 1839–1967, the first attempt at a comprehensive history of the field. Their book has been reprinted several times and was republished in a revised and enlarged edition in 1982. Brown was, briefly, in 1970, director of the Waikato Art Gallery in Hamilton before it merged with the Waikato Museum to become the Waikato Art Museum; and curator of pictures at the Hocken Library in Dunedin from 1971 to 1974. It was from there that he came to the Sarjeant.

With his strong professional background and clear-sighted view of what was needed, he embarked upon a rigorous programme of reform aimed at adapting ‘reasonably well-established principles of art gallery management to the situation in Wanganui’. At the same time he sought to raise the profile of the gallery through exhibitions, purchases and the writing of a collection management policy. He also founded a Friends of the Gallery, continued to upgrade the facilities and began assessing the extent and range of the collection.

His first budget estimate, for the year 1974/75, came to more than $33,000, an increase of $10,000 over the previous year’s expenditure. This was primarily to pay a registrar to begin the task of cataloguing the works in the gallery, both those in the permanent collection and those on loan, and to employ a part-time technician to assist with framing, mounting and myriad other practical tasks. Capital items included another upgrade of the lighting system, specifically to treat the skylights with ultra-violet inhibitors to allow the gallery to exhibit watercolours safely again. Brown also asked that council money be used, for the first time, to set up a picture purchase fund to augment the amounts already available from bequests.

The council pruned the budget, of course, but agreed to pay for a registrar and a technician, and to embark upon capital works, including ‘the installation of a goods lift, purchase of a reception desk and screen, redecoration of the dome and the foyer, installation of additional heating duct and basement fumigation together with glazing and lighting improvements’.

Brown also wanted to revitalise the gallery’s exhibition programme in order to strike a balance ‘between the desire for an ever-changing temporary exhibitions programme and the display of the gallery’s own permanent collection’. And he wanted to institute a purchasing policy, both to keep the collection up to date and to fill historical gaps. The new registrar, Deborah Maidment (later Frederikse), was appointed in 1975 (the first registrar of any gallery in New Zealand) and began to catalogue the collection. Kate Martin and then Jill Studd succeeded her.

In 1983, the research and cataloguing having progressed sufficiently, the show The Collection took over the entire gallery and traced developments since the Goldie was purchased in 1901. The print, photograph, cartoon and poster collections were excluded, for reasons of space, and the 700-plus paintings were exhibited in the order of their acquisition.

Also in 1975, Bill Milbank joined the staff as gallery assistant.

◆

William Handley (Bill) Milbank was born in 1948 in Raetihi and grew up on a 180-hectare mixed farm at Mangaeturoa, east of the town in the hill country towards Pipiriki on the Whanganui River. On the back of the wool boom that began at the time of the Korean War, Raetihi was in those days a solid, prosperous hub serving the local farming communities. It had a bookshop (Boyd’s), a cinema (the Royal), a Wright Stephenson’s and numerous outlets where you could buy what in those days were called mod cons. The substantial maternity hospital up on the hill at the end of Ward Street served the entire Waimarino district. When the farmers and their wives came to town they dressed in their good clothes and drove shiny latemodel cars. It was very different from the marginal rural town of today.

Milbank went to Mangaeturoa Primary, a 30-pupil country school, and then to Ruapehu College in Ohakune, to get to which he would cycle the 8 kilometres to Raetihi then catch the bus. The trades teacher at the college, Stan Frost, was responsible for a curriculum which included art, technical drawing, carpentry and the rest. Frost was a Londoner, a Cockney — born within the sound of the Bow Bells — and in person suave, handsome, sophisticated and enigmatic. He spoke Received Pronunciation rather than Cockney, dressed elegantly, cooked well, had a taste for liqueurs and liked to go trout fishing.

He told Milbank, who had a passion for art, that he was good enough to work professionally in the field. He also advised him that if he trained as an artist, he would probably end up as a teacher, but if he followed the technical drawing route, and qualified in architecture, he would be his own man.

Milbank could draw and usually came top of the class in that subject. However, he was also dyslexic and only got through his other school work with the help of a friend, Linda Rongonui, who would lend him her classroom notes each day so he could copy them out in the evenings. Linda was from a local family. Her grandmother had helped transform the Methodist church on the hill outside Raetihi into a Rātana temple. Ironically, Linda failed School Certificate, while Milbank passed. He subsequently got into trouble with a teacher — he was being pressured, as a prefect, to do a Bible reading at assembly, which his dyslexia made impossible — and left school early.

His father had injured his back and there was some talk of Bill taking over the family farm; his elder brother, Gorham, was away attending university. But Bill Milbank was enamoured of art. When he and his friend Paul Te Ua were paid on completion of their first scrub-cutting contract, he used his share of the money to buy a copy of anarchist, surrealist, existentialist Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting from Boyd’s bookshop. He was 14. After about 18 months on the farm, Milbank, who had already met the Whanganui girl who would become his first wife, went down to the city to live. There he felt, he remembered, ‘immediately at home’. The asthma and eczema that had troubled him on the farm both went into remission.

His family had deep roots in the district. His mother was a Handley, and his maternal great-great-grandfather had been chairman of the first town board and had a hand in the building of missionary Richard Taylor’s house at Pūtiki in the 1840s. During Tītokowaru’s War some Māori children were massacred by a combined force of Kai-iwi Yeomanry Cavalry Volunteers under John Bryce and Mounted Armed Constabulary under Captain William Newland at John Handley’s woolshed on his model farm, west of the city. Bryce, a local farmer turned politician, went on to lead the brutal and bloody invasion of Parihaka in 1880.

About a year after Milbank went to the city, his parents sold the farm and moved down as well. When he walked around the various architects’ offices looking for work as a draughtsman, Bill was told that jobs did come up from time to time and was advised, in the meantime, to seek some practical experience working for a building firm. He found employment with a local outfit, Madder and Bourne, as a builder’s labourer. He worked on the hospital, on the Winstone Building in Wilson Street — ‘from the ground up’ — and on renovations to the old Herald building. Within a matter of weeks he had shown such an aptitude for reading plans that he was being called upon to assist the leading hands in applying them to the construction work they were doing, and so began to specialise in that area.

After about nine months a draughtsman’s job came up in the town planning department of the council. Milbank worked there for the next seven years. This gave him experience in a number of areas: dealing with the general public, especially when facilitating (or not) building permits for people from all walks of life; developing and processing planning ideas, for instance for a proposed redevelopment of Whanganui East which did not, in the end, go ahead; and, more generally, providing the best and soundest technical advice to those elected by the community whose job it was to make decisions.

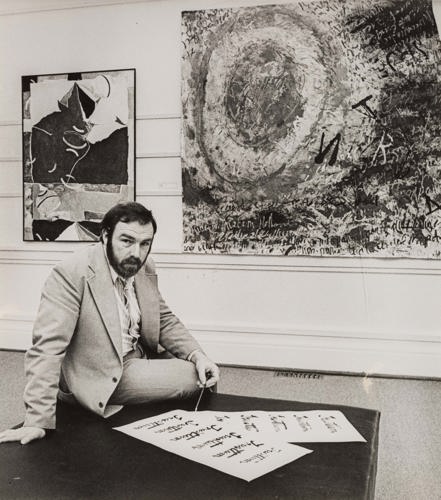

In 1974, with his wife Johanne, he set out on an extended overseas trip: to Australia, to Portuguese Timor, then on through south-east Asia as far as northern Thailand before flying to India; thence via Moscow to London. They spent eight months crisscrossing Europe in a Kombi van, visiting galleries and churches, looking at art ‘all the time’. There was a revelation in Toledo, in front of an El Greco, when Milbank understood a hitherto obscure (to him) connection between these works and a painting he had admired on his weekly visits to the Sarjeant. He wondered, naively, if the Sarjeant painting was in fact by El Greco. It turned out to be the aforementioned Gethsemane by New Zealand artist Lois White.

At the time of his appointment to the Sarjeant, Milbank was back from overseas and working in a plastics factory in Gonville, making faux marble vanity cabinets for bathrooms. His father worked there too. Bill recalled:

I knew nothing of New Zealand art. I had no appreciation of who was relevant and who was not relevant from a New Zealand perspective. Maybe the name McCahon sat somewhere. But that Lois White painting was pivotal to my thinking process and made me aware. Wow, that’s from New Zealand, what else? And then I arrived on the doorstep of the best teacher I could ever have had.

He meant, of course, Gordon Brown.

◆

Over the next year, 1976, considerable progress was made towards bringing the gallery up to a standard of management appropriate for a professional institution, but there were still battles to be fought. Differences of opinion developed between the director and the council on various matters. The most intractable was the question of access to the gallery for local art groups. Every year the Camera Club, the Potters’ Society, the Spinners and Weavers and the Art Society held their annual exhibitions at the Sarjeant. Since half the gallery, at any one time, showed works from the permanent collection, this meant that effectively a major proportion of the gallery’s exhibiting year was given over to such societies.