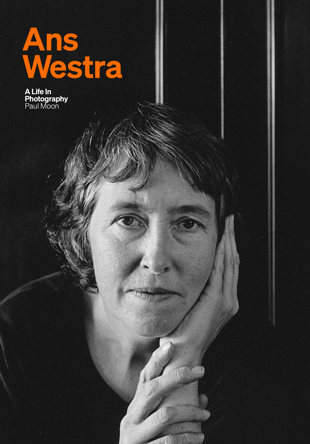

Jenny Nicholls reviews Ans Westra: A life in photography by Paul Moon for Waiheke Weekender:

‘A gentle biography of the photographer who took some of the most controversial photographs ever made in New Zealand. Ans Westra (1936–2023) is known for her photographs of Māori, Pākehā and Pasifika, ‘slices of life’ which many believe rank among the greatest images of midcentury photographic art.

But Westra has had her critics. As a Dutch-Kiwi female ‘interloper’ in Māori and Pasifika culture, Westa’s work, most notoriously the 1964 children’s book Washday at the Pa, to some exemplifies an arrogant ‘Pākehā gaze’, one which still stereotypes Māori as poor and rural. Washday was withdrawn from school after the Māori Women’s Welfare League complained it did not represent Māori fairly.

This is a complex complaint. To debate her work requires an understanding of Westra's process.

It was always unfair to accuse Westra of posing her subjects, to ‘contrive’ her photographs, as some critics still do. (Not many of them are photographers!).

Westra was known for working unobtrusively, to capture people behaving as naturally as possible. This was her thing, her process. To most people who look carefully at her photography, this is blindingly obvious.

‘Reportage’ photography like this is exacting. It requires an ability to compose the image in seconds. If you miss the moment, it has gone forever.

When Westra arrived in New Zealand, she encountered a very different tradition, of dressed-up, postcard portraits of Māori taken by studio photographers who commanded their subject's every strand of hair. Westra’s own approach could not have been more different.

Author Dr Paul Moon, a professor of history at Auckland University of Technology, lets Westa’s critics have their say, and is not unsympathetic to some of their arguments — notably the view that Westra was often ‘naïve’ and made mistakes when photographing sensitive events like the funeral of her good friend James K. Baxter. But he intends his book to stand as a corrective to misrepresentations of her work, and he reveals important information about the photographer’s state of mind, her artistry and interactions with the people she photographed.

According to Moon, many of the Washday whānau valued Westra’s images highly, placing one of her portraits of a family member on a headstone after their death.

Westra died in 2023, as Moon was writing this book, but not before he had spent some time talking to her about her life and work. He was also able to talk to her children Lisa, Erik and Jacob, and made use of interviews with Westra by Hugo Manson, a co-found of the New Zealand Oral History Archive.

Westra left behind an incredible body of work — some 325,000 images — while enduring storms of public criticism and periods of mental illness. As a migrant with a wartime childhood which included sexual abuse, Moon reveals Westra’s bouts of loneliness and isolation, inexpressibly poignant in a photographer who loved to capture ordinary human warmth and interaction.

Her work took courage, determination and curiosity; very few New Zealand photographers with her level of skill went to the places she did. If her work was art, it was also something else — an irreplaceable record of New Zealand Māori, Pasifika, working class, gang and student life, scenes from an underground Aotearoa some seem to wish was never recorded, at least as well as this. Photojournalism has long been a contested and undervalued artform in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Even the word is unpopular, usually replaced with the passive term ‘documentary’.

While Westra had the humanity, compositional sense and technical skill of a great photographer, a W. Eugene Smith or Dorothea Lange, she was often poor. Her photography, explains Moon, was a compulsion: like many artists her work, she felt, kept her sane.

This is a fascinating and well-researched biography written with clarity and compassion, and deserves to puncture fact-free critiques of Westra’s work.

There’s just one thing. As a text driven biography, however ‘richly illustrated’, Westra’s pint-sized half-page photographs (printed on paper which doesn’t do them justice), play second fiddle to the text. I hope this isn’t it for Ans Westra. We await a comprehensive, beautifully printed coffee-table book size collection of Westra’s work, along the lines of Marti Friedlander: Photographs, or Vivian Maier: A Photographer Found.’