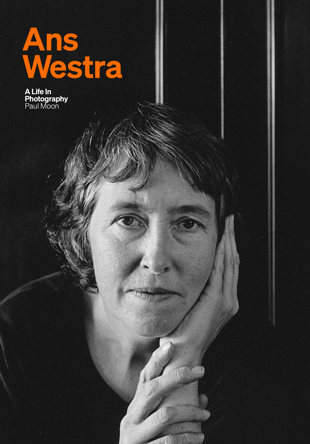

Mary Macpherson reviews Ans Westra: A life in photography by Paul Moon for Art New Zealand:

‘For nearly 70 years, Ans Westra photographed the life of Aotearoa New Zealand and its people, taking an estimated 325,000 images. In his insightful biography, Dr Paul Moon makes the case for the contribution Westra's work has made to our sense of identity: 'Collectively, these are the closest the country has to a national photo album', he says. A large quantity of her images is publicly accessible, particularly through the National Library, meaning that her vision of New Zealand identity will be long-lasting. Small wonder we are curious about the single-minded maker of the photographs; the person, the vision she had of her image-making, and the social and cultural settings in which she worked.

Westra died during the writing of this biography but Moon explains he drew on a 'wealth of material including interview transcripts' and he stitches together a nuanced, comprehensive picture showing her significant strengths and limitations, the times she lived in as well as her own view of her life and work.

Although Westra's photographic career continued until her death in 2023 at age 86, and her subjects and publications were varied, her prominence is particularly linked to photographs of Maori in the 1960s when she often had access to parts of a Māori world unknown to Pāhekā. Inevitably, like a long-running curse, when her work is mentioned there follows reference to the withdrawal of her 1964 Washday at the Pa booklet by the then Minister of Education after resonant criticism from organisations like the Māori Women's Welfare League ‘arguing that it portrayed a negative, dated and stereotypical view of Māori'.

Moon canvasses this debate thoroughly, and its changes over time, but what he brings fresh to the topic is an understanding of how Westra's approach led to the Washday photographs. He talks of how her images were 'beginning to challenge some of the clichéd views held by Pākehā New Zealanders about Māori' and 'her genius' in identifying 'cultural fault lines' like the flux of rural and urban Māori culture as Māori moved to the city, often remembering what they had left behind. In these observations we see the vital force of Westra's documentary photography and understand her engagement. But photographing another culture as an outsider, and shaping those images for publications, has pitfalls.

Moon devotes his preceding chapter to Westra's 1962 Pacific Islands visit where she created Viliami of the Friendly lsles, a children's publication about life in a Tongan village, issued by the Department of Education. 'The images were supposed to inform New Zealand school children about how their counterparts in Tonga lived . . . but Ans consciously set out to accentuate differences', Moon says. The photographs are in her usual style, emphasising human connection. But, he says, the publication ‘was also a form of reality creation. It reinforced concepts of a stylised South Pacific utopia, which framed the way its residents were understood by outsiders.’ But as School Publications welcomed Viliami, Westra and others felt its ingredients, 'its focus on youth and everyday activities in a different cultural setting, were a recipe worth repeating in a New Zealand context'. And so we understand the short step to the Washday project.

Westra initiated and featured in many books, drawn like photographers today to the power and creativity of long-form visual narrative. She was one of Aotearoa's pioneering photography bookmakers with seminal works like Maori, described by John Turner and William Main as 'perhaps the finest New Zealand photographic book of the sixties', and Notes on the Country I Live In. Later publications showed her shifting direction with ventures like Wellington: City Alive and We Live by a Lake, both with novelist Noel Hilliard, The Crescent Moon and Handboek: Ans Westra Photographs—a career survey—and later in life the environmentally focused Our Future: Nga Tau ki Muri.

Moon outlines the thinking behind the works, her struggles to control layouts and quality, and the effect that, sometimes unsuitable, writers had on the work. He is adept at drawing attention to important photographs and sequences. Commenting on the opening rainy-day photograph in Wellington: City Alive he praises the 'brilliance of its composition' which ends in individuals who 'stand in a thin line waiting to cross the road. For all their variety—men and women young and old, shoppers and workers—they all look united in a wish to be anywhere but there.'

Throughout the biography, attention is drawn to Westra's telling photographs, the ones where she has captured a piece of social commentary or interaction but with her potent 'fly on the wall' approach allowing viewers to make up their minds about it. He is also aware that her style can be seen as artistically unvarying, quoting Te Papa Curator Photography Athol McCredie: 'I don't think she pushed any boundaries in terms of photographic approach, stylistic approach, formal approach, artistic approach. It was more she pushed boundaries . . . of subject matter and that business of persistence.' To the criticism that her style was dated, Moon counters that this was transcended by 'her ability to capture a gesture, an expression or a sentiment'.

He gives enough information about Westra's private life to make us appreciate her lifelong tenacity that kept her filling the pages of the photo album, even after she was recognised as one of Aotearoa's important photographers. Her childhood in Holland included an abusive stepfather, which Moon speculates might have had an effect on her personality and surfaced in a mental health episode in later life. She also lived by the precarious business of freelancing, seeking assignments that supported her vision and raised three children, in part as a single mother in an era in which that choice was not supported.

Commenting on the importance of her culture-building work, particularly for younger viewers, Moon concludes: 'Ans probably accomplished as much as any other individual in the country's history when it came to constructing a vision of New Zealand's identity. And, as Desmond Kelly put it, "The country is richer for it."'

Ans Westra: A Life in Photography provides valuable insight into the work and life of the woman behind that identity.’