Theo Macdonald reviews Ans Westra: A life in photography by Paul Moon for North & South:

‘Unpacking required.

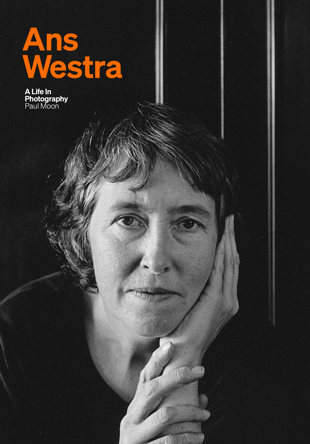

A photograph can tenderly trace a precise slice of time and place, yet the medium has so often been deployed by artists, advertisers, states and insurgents in the mission of fey universalism. The medium's troubled dichotomies — specific versus general, truth against fiction — are particularly the problems of social documentary photography. In New Zealand's 180-odd year photographic history, there is likely no practitioner of social documentary more celebrated than Ans Westra (1936–2023). Ans Westra: A life in photography, by prolific historian Paul Moon (ONZM), tells Westra's story “through her eyes”, drawing on interviews and a rich archive.

For any biographer, Westra's life is sensational material. Four years old when the Nazis occupied the Netherlands, by eight she was distributing anti-Nazi literature on behalf of the resistance. After the war, her parents separated. Her mother Hendrika married a paedophile whose molestation of young Ans the adult Westra preferred not to discuss. Under a cloud of tax fraud, Westra's faster Pieter fled to Indonesia, before settling in New Zealand in 1950. Pieter invited Westra to join him in the late 50s. She was already a keen photographer, and hoped a new country would bring creative opportunities. Westra found work on the Crown Lynn production line then moved to Wellington to avoid her father, who implied he had only invited her to join him as a way of getting back at Hendrika. In 1960, she made her first photographic sale to Te Ao Hou, a magazine published by the Māori Affairs Department, who, along with the Department of Education, would remain a regular client in these early years.

The biography's first act turns, naturally, on Washday at the Pa. With text and photographs by Westra, Washday was released by the Department of Education in 1964 and soon withdrawn at the request of the Māori Women's Welfare League. This group, alongside other Māori critics, argued Westra's representation of poverty-stricken, rural Māori family life perpetuated damaging, atypical stereotypes. The dispute wounded Westra. It challenged her relationship with the only thing she could rely upon — her creative judgement.

The fallout from Washday at the Pa irradiates the remainder of this biography, mutating it into an apologia, “a corrective to...misrepresentations of her work.” Moon writes, “[...] some argue that the fact that an artist depicting Māori is Pākehā is all that is needed to confirm that those Māori have been “othered”, and that these words exoticise or marginalise their subjects, no matter how much cultural empathy the artist may have had.” He continues, “The risk in unleashing such arguments, and allowing them to roam freely, is that both the aesthetic merits of the art and its documentary importance can be subsumed by the theoretical brawls from which no one emerges as a winner.”

Westra's photography possesses rare psychological intensity. In her recurring images on favourite themes, including children, urban landscapes and Māori communities, the psychological turmoil and innocence she projects onto her subjects is stark and persuasive. This does not mean we shouldn't unpack her artistry. Moon's engagement with Westra's work is limited by her own self-definitions. She describes herself as neutral despite how deliberately she selected which negatives to print — editing is storytelling.

Mere moments after describing how her work in Tonga “reinforced concepted of a stylised South Pacific utopia...”, Moon writes that Westra was “determined not to push any particular ideological barrow”. He claims her photography was not entwined with colonial ideas of Māori as a people in decline, yet later quotes Westra describing the urgency of her salvaging this culture before it disappears. When Westra waits for a child to be distracted, before snapping the lens, that feigned authenticity is far more unsettled than Moon's “corrective” wants us to believe.

The book's critical thinness is encapsulated in Moon's breezy summation of The Family of Man, a titanic photography exhibition which toured the world for eight years, containing, in the words of curator Edward Steichen, “the individual family unit as it exists all over the world and its reactions to the beginnings of life and following through to the death and burial.” Westra saw the exhibition in Amsterdam as a child, where it “awakened Ans' mind to some of the possibilities of the relatively new genre of photography.” Moon returns many times to The Family of Man to emphasise its influence on Westra's humanism and documentary values.

What isn't addressed is the exhibition's role as a foundation stone of photographic criticism. Roland Barthes wrote, “by purporting to show that individuals are born, work, laugh, and die everywhere in the same way, The Family of Man denies the determining weight of history — of genuine and histortically embedded differences, injustices, and conflicts.” Others similarly criticised the exhibition's sentimental universalism.

If, as Moon argues, Westra's practice is the “New Zealand photo album”, this photo album is worth more as a messily annotated collective effort — respecting the diverse, ongoing critical evaluation of her work — than sealed in museum glass.’