Pinky Agnew’s launch speech for Old Black Cloud, by Jacqueline Leckie, Unity Books Wellington, 12 June 2024

Thank you Nicola, thank you Jacqui.

It is my great honour to launch this important book, painstakingly researched and beautifully written by Dr Jacqueline Leckie.

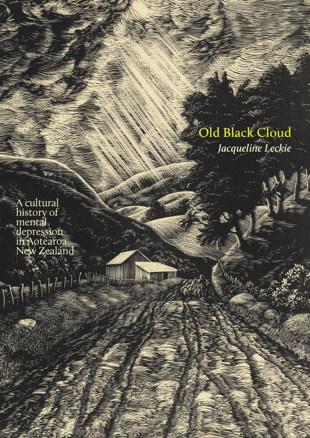

It is, as it says on the exquisitely evocative cover, a cultural history of depression in Aotearoa New Zealand. It is, for me as a reader, a collection of stories of people living with depression. The book speaks too of medical and psychiatric treatments, of society’s attitudes and laws, of everything from quack remedies to fads and fashions in psychiatry - all giving a rich context and historical timeline which enhance those personal stories.

It is the personal stories in this book which drew me in as a reader, each one representing not just a person, but their whanau and their descendants. This makes this cultural history so important, so compelling.

People may think it’s strange to have a comedian launch such a book. Two stereotypes exist for people who are branded as comedians. One is of the jolly person, always making a joke, never taking anything seriously. Think Phyllis Diller. The other is of a tragic clown, whose smiling mask hides a sad person. Think Robin Williams. Neither is true. Like anyone else, my personality, my story is more nuanced.

Jacqui’s book arrested my attention right from the first words in the introduction, where she briefly traces her own and her family’s history of depression. She evocatively describes how she felt after finally finding the right treatment with the right psychiatrist.

“I still recall walking along the Devonport waterfront in 1980, and seeing the sun setting, smelling the sea, hearing the waves and the seagulls and feeling the warmth of the day. For at least the previous year I had felt absolutely nothing except pain.” I too have felt that, just as I too have felt the bleakness of the black cloud of depression, as have my siblings.

My name is in the book, but it’s not my story.

The family story which is touched on in Jacqui’s book is the story of this woman, which you can read on pages 107-108, in the chapter called ‘The Lonely Land’.

Jane Samson Jeffries Dick, born in Scotland in 1888. This photograph sat on our mantlepiece throughout my growing years. I knew she was my grandmother. What I did not know was that she was still alive. Each of us siblings has a story about how we found out that Grandmother was alive and living in psychiatric care. Mine was this.

Ten- year-old me stood at the fridge, holding a jug of milk. My mother, sitting at the table says oh so casually, “I’m going to see my mother in Cherry Farm. Would anyone like to come?” I squeak, “Your mother?” The milk jug slips from my hand and bangs down onto the top shelf of the fridge. Milk sprays up and hits my cheek, rolling down it like tears.

I didn’t go and visit her. I never did. Although I did see her once when we were, coincidentally in hospital at the same time, not long before she died. She was in her 80s when she died. She’d lived in care for over fifty years, being first committed to Seacliff Asylum near Dunedin when my Mum Jean was a baby and her brother Jock a toddler. She had been found walking purposefully with her two small children over a paddock towards a cliff on the Otago Peninsula. She went on to live in Cherry Farm and Orokonui hospitals before dying in the 1970s.

Mum told me later that her mother’s diagnosis initially was post-natal depression. My grandmother Jane, this brilliant, beautiful woman, a theatre nurse who sang solos in St Gile’s Edinburgh, was, like so many of the people whose stories are also told in this book, a migrant to Aotearoa.

She came, full of hope, a war bride in 1919 with her Kiwi husband, to a desolate new home in a remote community. When Jacqui researched my grandmother Jane Dick’s story for this book, she wasn’t able to access her health records.

So, when I call Jacqui’s research ‘painstaking’, it means each human story in this book was a direct result of Jacqui uncovering it, checking it, verifying it, and writing it with honesty, compassion and sensitivity. All the while, as you will read in her introduction, dealing with her own ups and downs and depression.

The stories of migrants experiencing depression weave in with Jacqui’s previous work recording mental health throughout the Pacific, as well as recording the stories of migrant populations in Aotearoa New Zealand, especially from India. Importantly, Old Black Cloud devotes a chapter to Tangata Whenua’s experience of mental health pre- and post-colonisation. That chapter alone must become compulsory reading for anyone working in health in our country. The epilogue of Old Black Cloud brings the reader the good news and the bad news of modern mental health in Aotearoa.

Like my grandmother, the poet Meg Campbell was first admitted to a psychiatric hospital with postnatal depression. Jacqui quotes from Meg Campbell’s poem Heredity in her book. This ‘most unwanted gift – that of a blighted mind’. Even as a ten-year-old, learning of my grandmother's existence for the first time, my primary emotion was fear. That I too would carry this most unwanted gift, and would end up like my grandmother, as my cousin later said “in the loony bin for life.” Thankfully, as Jacqui documents in this magnificent book, we are already moving towards a brighter and more understanding future for those of us who live under the old black cloud.

By permission from Pinky Agnew, MNZM