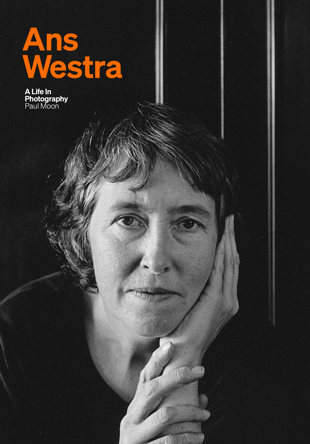

Max Oettli reviews Ans Westra: A life in photography by Paul Moon:

‘Everyone seems to have an Ans Westra story to tell. Mine involves Westra swearing in Dutch in the tub of my dark bathroom while standing barefoot in broken glass from a busted lightbulb one chilly Dunedin predawn morning. So one surmises her biographer Paul Moon would have had an overload of anecdotal information to consider, and much of the work on his authoritative bio would have been essentially cutting away the undergrowth of scrub—or gossip or what you will—to get to the heartwood of her remarkable life.

She was precious, tall and conspicuous, a kauri of the forest, while her output was huge, remarkable, and even overwhelming. She courted a number of controversies, not all of her own making, as late twentieth-century New Zealand history swirled around her. Her archive is an iconographic backbone for any sweeping study of the 1960s to the 2000s in this country. Many photographs have become classic, defining images with a quality and poise rarely achieved by her contemporaries. They’re packed with instinctive energy and factual details that ensure they will live on long past her lonely death last year.

Moon, the historian, has had the patience to stare hard at her work and the skill to describe it evocatively. Here, he is looking at a Westra photograph of James K. Baxter that shows him in his last year—a time of manic and ubiquitous activity—preaching in a Catholic church. (And Westra, too, was busy—as Moon says, it was for her a ‘professionally productive but personally tumultuous period’.)

The black and white photograph is a ‘study in religiosity and light. The image is dominated by the white walls and ceiling of the church’s interior and the altar, itself a stark white in the light from the adjacent windows. Far from the embracing aura of white that had become a cliché in religious art, this white is lifeless and cold.’ Moon writes of the foreground showing ‘a counterbalance by the backs of rows of dark timber pews … a soft dark blur that contrasts with the sharp whites’. Baxter is standing at the lectern, modestly dressed, hands clasped and looking down at the bible from which he is reading. ‘His long hair, his draping beard and his gaunt physique convey a John the Baptist-type impression. Above his right shoulder is a standard statue of Christ with a Sacred Heart. The comparison between the two is sacrilegious.’ (Well, yes, but the sacrilegious pose is one that Baxter, by the early 1970s, was working to the hilt.)

‘Baxter’s public image was at its height at this time,’ Moon continues, ‘and his fame attracted followers.’ I’m a little dubious about this implied cult-like following; certainly not in my circles, including the fucked-up junkies I knew. Moon goes on to point out that the church in which Baxter is reading is essentially empty: ‘This scene, in which the crowds have abandoned Baxter, foreshadowed the collapse of his community, and his own imminent demise.’ Moon cannot resist a little sermonising of his own. May we suppose his followers were too stoned to attend church?

He includes Westra’s comment, ‘I can’t say he was a fraud’, on which he then elaborates: ‘[but she] could see that Baxter was all too human, and possessed the frailties and shortcomings that went with that’. To borrow a line from Friedrich Nietzsche, the poet was ‘human, all too human’. But if Baxter was a man with ‘frailties and shortcomings’, Westra also had ‘a knack for choosing wrong partners’. She was in a messy and turbulent relationship with Barry Crump for a while, and we somewhat pruriently learn of the conception of their son Erik, involving a great deal of booze and her VW Beetle pulled over in the chilly hills of Wellington. The VW, which she imported from the Netherlands in 1966, was a good and faithful servant hauling her hither and yon. VWs were a miracle of Porsche design that never broke down. And she’s never without her equally reliable Rolleiflex camera.

The first chapter of this book, dealing with Westra and the German occupation of Holland that lasted until her tenth year, is diligent and illuminated by snippets from Moon’s unique taped conversations, made in February 2022. We learn a few details about the family business and of her terror at seeing an infant being crushed by a German Panzer. Inevitably, there was the traumatic numbness that gripped many Netherlanders from that generation, post-War. ‘You saw nothing,’ her mother told four-year-old Ans, who, in fact, remembered what she witnessed. Later, she carried messages for the Dutch Resistance.

However, what really counted was her gradual discovery of photography. The legendary Rolleiflex was, in those days, the world standard in quality and reliability. Above all, it has a mirror-reflex viewing set-up, which allows us photographers to photograph discreetly through a Zeiss lens without having the camera distractingly in front of our faces. I’ve worked with them myself as a press photographer in the 1960s and 1970s, often with a powerful flashgun humming and tunnelling through semi-darkness. The frontal but head-down style this camera allowed, both non-confrontational and all-seeing at the same time, created a distinctive ambience around a lot of her early work in this country.’

Read the rest of the review here.