‘The first Pasifika poet of the modern diaspora to emerge in Aotearoa New Zealand was Alistair Te Ariki Campbell, who was born in Rarotonga in 1925 and who died in Wellington in 2009. His father was a trader from Dunedin and of Scottish ancestry. His mother was from Tongareva in the northern group of the Cook Islands.

Campbell came to New Zealand at the age of eight with his siblings, after the death of both of his parents. The children grew up in an orphanage in Dunedin. Campbell began writing poetry at high school, and in 1950, after graduating from university, he became the first Polynesian poet to have a collection of his poems published in English. This book, Mine Eyes Dazzle, published by Pegasus Press, was critically acclaimed and led to Campbell being acknowledged as ‘a master of language’.

For those of the Pasifika diaspora, there is the Pacific we carry in our heads and there is a Pacific which is the site of various contestations. Campbell encountered racism in his daily life in mid-twentieth-century New Zealand, and subsequently downplayed his Polynesian identity, but his early poems are lyrical and rhythmic and animistic in a way that draws directly on his Polynesian background and intuitions. One of his best-known early poems, ‘The Return’, is full of foreboding as it speaks of ‘the surf-loud beach’, ‘mats and splintered masts’, ‘plant gods, tree gods’, and ‘fires going out on the thundering sand’.

Campbell’s sense of alienation from his Polynesian roots — ‘the Polynesian strain’ as he called it — contributed to a series of nervous breakdowns that took him years to overcome, and the healing process as a creative writer involved his return to Rarotonga for the first time in 1976. This led to a new creative efflorescence, beginning with his collection Dark Lord of Savaiki, published by Te Kotare Press in 1980.

The Cook Islands, Niue and Tokelau have a special relationship with New Zealand, established in the colonial era. As a result, their citizens are New Zealand citizens and have the legal right to live here. Those from Sāmoa, Tonga and elsewhere in the Pacific require visas. The mid-1970s are now remembered as the era of ‘dawn raids’, when heavy-handed immigration officials targeted Pacific Islanders in their homes in the early morning in search of those whose visas had expired.

But by the mid-1970s New Zealand had also become a country with a sizeable Polynesian population, and a new cultural assertiveness had begun to manifest itself. Pacific Island groups, such as the Polynesian Panther Party and members of various church denominations, established themselves as community activists, aligning with other political activists such as the Nuclear-Free Pacific movement and the anti-Springbok Tour movement, as well as with protesters seeking Māori self-determination and recognition of land rights. Colonial legacies began to be questioned and challenged.

In 1976 Albert Wendt, recently appointed lecturer at the newly-established University of the South Pacific in Fiji, produced his landmark declaration ‘Towards a New Oceania’, which called for the recognition of an Indigenous Polynesian literature. It was printed in the inaugural issue of Mana Review: A South Pacific Journal of Language and Literature, produced by the University of the South Pacific Press. In this manifesto Wendt stated: ‘Our quest should not be for a revival of our past cultures but for the creation of new cultures which are free of the taint of colonialism and based firmly on our own pasts. The quest should be for a new Oceania.’

Wendt was born in Apia, Sāmoa, and moved to New Plymouth, New Zealand, as a scholarship student in 1953, when he was thirteen years old. The publication of his acclaimed first novel, Sons for the Return Home, in 1973 was a defining event for modern Pasifika literature, establishing Wendt as a pre-eminent Polynesian writer. In 1976, the publishing firm Longman Paul in Auckland released Albert Wendt’s first poetry collection, Inside Us the Dead: Poems 1961 to 1974. Like Alistair Campbell, Wendt had begun writing poems at high school.

In 1980 a weekly poetry reading event called Poetry Live, open to all, was established by the Pālagi poet David Mitchell at the since demolished Globe Hotel in inner-city Auckland. This lively and popular performance space featuring established poets as guest readers soon attracted a variety of younger Pasifika poets to read their work, including David Eggleton, John Pule, Albert Livingston Refiti, Serie Barford and Gina Cole. David Eggleton was already producing self-published broadsheets of his poems, while John Pule produced his first self-published poetry pamphlet, Sonnets to Van Gogh, in 1982.

Eggleton and Pule began occasionally performing together, busking their poems at venues such as Cook Street Market. In 1983 they launched a national poetry performance tour as Two South Auckland Polynesian Poets (Eggleton grew up partly in Māngere East, while Pule grew up partly in Ōtara), supported by what was then the Māori and South Pacific Arts Council. Later that year, both poets took part in a key series of readings by Indigenous writers entitled ‘Māori Writers Read’ at the Depot Theatre in Wellington, alongside Alistair Te Ariki Campbell, Witi Ihimaera, Apirana Taylor, Patricia Grace and others.

Like Campbell and Wendt, as Pasifika poets and storytellers Eggleton and Pule were products of the colonial classroom, having its stereotyping and profiling drummed into them and consequently struggling to deal with a sense of cultural diminishment and imbalance. As Albert Wendt stated in the Mana Review manifesto, it was necessary ‘to free ourselves of the mythologies created about us in colonial literature’.

Other Pasifika writers, too, felt the pressure. In an interview with Maryanne Pale on Creative Talanoa, Serie Barford described how she struggled to cope with the New Zealand university system: ‘I was brought up the old way with the church and with chaperones and found myself alone in a strange place at the height of the feminist movement in the late 1970s. Every time I opened my mouth in a tutorial I felt like I was being mocked and that my world view was being ridiculed.’

Gradually, though, things began to change, especially after the 1984 election of the progressive Fourth Labour Government under David Lange and the subsequent declaration of a nuclear-free New Zealand, which helped establish a new sense of identity based in the South Pacific. However, overcoming conservative prejudices remained a work in progress; Pacific Islanders continued to be treated as political scapegoats in the media and continued to be confronted by urban alienation, economic disadvantages and a precarious migrant status. For the dominant Pākehā settler culture, the Pacific persisted as an exotic ‘elsewhere’ and Britain remained ‘the mother country’.

But by the early 1990s, evidence of the cultural turn towards Aotearoa New Zealand’s geographical location as a South Pacific nation was being acknowledged more and more. David Eggleton’s first collection of poems, South Pacific Sunrise, was published by Penguin Books in 1986; it was co-winner of the Jessie Mackay Best First Book Award for Poetry the following year. Albert Wendt returned to New Zealand as Professor of New Zealand Literature at the University of Auckland in 1988. Samoan poet and artist Momoe Malietoa Von Reiche, then living in Northland, became notable in 1989 when New Women’s Press published a substantial collection of her poetry, Tai — Heart of a Tree. John Pule’s first novel, The Shark that Ate the Sun (Ko E Mago Ne Kai E La), was published by Penguin in 1992.

Pacific Islanders were now becoming prominent in many cultural areas of endeavour in Niu Sila, from dance and theatre to art and music. The rock band Herbs, founded in 1979 by Samoan vocalist and songwriter Toni Fonoti — who said he wanted ‘to put Pacific influences into music, make Island culture more available, give it a modern soul’ — produced a number of anthemic recordings, including the era-defining, anti-nuclear-testing protest song ‘French Letter’.

In the 1990s there was a surge of Pasifika musical artists creating highly articulate rap lyrics and song lyrics commenting on social issues — from Sisters Underground (with Brenda Pua) and OMC (Pauly Fuemana) to King Kapisi, Che Fu and the group Nesian Mystik. In Papatoetoe, South Auckland, the recording label Dawn Raid Entertainment, repurposing traumatic memories of the dawn raids, signed up a raft of Pasifika hip-hop artists and released their party and dance music.

Community-activist Pasifika poets of the 1990s included Reverend Mua Strickson-Pua, an ordained church minister who mentored Pasifika youth at the Tagata Pasifika Resource Centre in Auckland, encouraging them as poets and performers. Rosanna Raymond was another artist, writer and poet who came to prominence in the mid-1990s in Auckland as a founding member of the Pacific Sisters art collective, celebrating mana wāhine.

In 2000, Teresia Kieuea Teaiwa was appointed the inaugural programme director of Pacific Studies at Victoria University in Wellington. A poet, theorist and academic, Teaiwa grew up as part of the resettled Banaban community on the island of Rabi in Fiji and undertook postgraduate university studies in the United States. Like Albert Wendt earlier, in the 1990s she became a pivotal figure in connecting Pasifika literatures across Oceania as a regular presenter at conferences and other events, using the concept of the vā.

In his 1993 essay ‘Our Sea of Islands’, published in the book A New Oceania: Rediscovering Our Sea of Islands produced by the University of the South Pacific Press, Tongan writer Epeli Hau‘ofa, a leading light based in Suva, pointed out that nineteenth-century imperialism erected boundaries that led to the contraction of Oceania, ‘transforming a once boundless world into states and territories’. A return to Indigenous concepts was needed to re-establish a sense of unity and interconnectedness, he wrote. The vā is just such a concept; it’s the traditional dynamic space that holds Pasifika peoples together as a group; it is the sea between islands.

In his 1993 novel Ola, Albert Wendt wrote about the vā as a metaphor for connection, integral to Polynesian thought, serving to define relationships:

Our vā with others define us.

We can only be ourselves linked to everyone and everything

else in the Vā, the-Unity-that-is-All and now.

Wendt proposed the vā as acknowledging a vast interconnecting fakapapa, recognising the interrelational spaces between people and their environment as an act of imagination. As he wrote in 1976 in Towards a New Oceania: ‘Oceania deserves more than an attempt at mundane fact; only the imagination in free flight can hope — if not to contain her — to grasp some of her shape, plumage, and pain.’

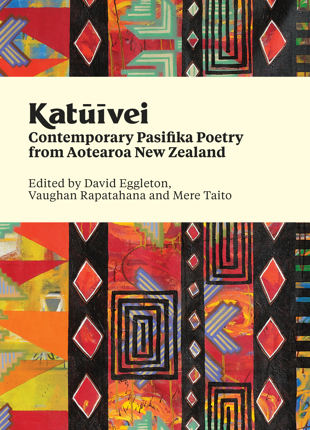

Teaiwa echoed this sentiment, stating in an 2015 interview with the journalist Dale Husband for E-Tangata: ‘It’s my job to remind people of the complexity [of the Pacific] and not let them try to paint us with a single brush stroke.’ The Moana Nui is a complex hybrid entity, and we have sought to represent this paradoxical reality through the editorial mix of contemporary poems in Katūīvei.’

. . .

Katūīvei: Contemporary Pasifika poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand ships 11 April. Order here.