Q1: Was it an immediate ‘yes!’ when ‘kōrero series’ mastermind Lloyd Jones asked whether you’d like to work together on this?

BF: When Lloyd phoned with the proposal, I was filming up in the Knobbies Range near Alexandra. The line wasn’t clear and my hearing isn’t brilliant. All I caught was: kōrero, Chris Price, a lobster’s tail (sic) and, photographs of water. Of course I said yes.

CP: It was a really fast yes, and also a leap into the unknown. I’d normally have spent some time searching for the ‘right’ artist — but when Lloyd and I had a coffee to toss around ideas for who to choose, my spur of the moment idea was that perhaps the art should have ‘something to do with water’. Next minute Bruce was a done deal. I’d seen individual photographs over the years, and knew he was one of a group of artists who travelled to the Kermadecs for a project about oceans, but I’d never seen a full solo exhibition of his work. It was only afterwards that I remembered having seen and loved the group show Wai, which Bruce co-curated with Greg O’Brien, at Pataka in 2020.

Q2: Had you worked together before?

CP: I’d met Bruce briefly through his partner Kate De Goldi, but never dreamed that we’d end up as collaborators. Lloyd’s instinct in putting us together was sound, and the results are actually far better than if I’d chosen the artist myself. I alternate between control-freakery and improvisation in making work: this was a true voyage into the unknown, which is what Lloyd wants for these books.

Q3: What’s the particular delight that comes with such collaborations between writer and artist?

BF: Partnering with Chris brought many delights. Initially it was the delight in getting to know someone who is warm and friendly, a musician and writer and researcher into arcane subjects. She’s insightful about photography, in particular the metaphorical possibilities of the medium. This was a huge asset in the collaboration. We also have similar tics which meant we weren’t frustrated by each other’s. We’re both perfectionists and like to tinker and fiddle. (Chris is worse than me!) However, she is less impetuous and that was a big plus. A better result and fewer regrets. Chris also likes a beer over lunch, which I think is very civilised.

CP: I’m glad Bruce said that about the endless tinkering and perfectionism: it makes me feel a bit better about driving him nuts. Give and take is fundamental to collaboration: if you have two people who want to be captain, your ship will end up on the rocks, but I think we were able to respect each other’s most deeply held convictions and desires when it came to the look and feel of the book! We both care deeply about design and typography, and the collaboration is as present in our shared passion for those aspects of the book as in its text and images.

I’m deeply envious of the wordless artforms (music and dance, as well as photography) for their ability to suggest things that live beyond words, so being able to set the text in a kind of dance with the photos was incredibly exciting. They enlarge rather than illustrate the essay, and the beautiful and disturbing, semi-abstract images of degraded land- and waterscapes in particular inspired a whole new line of thinking about things that were present but more submerged in the essay; they move it towards a more developed environmental conscience. Art and words come into a conversation that neither on its own would have had, and both are changed by it.

Another delight was being able to share the lobster obsession and pass it on: Bruce started feeding me new tidbits of lobster lore, and the Madagascan lobster was added to the essay very late in the piece thanks to an article he sent me.

Q4: And the challenges?

BF: The challenge was the task itself. The collaboration was only ever stimulating and motivating and the chance to be less myopic about my own work; to also see it through the eyes of someone whose insights and instincts I quickly came to totally trust. Working with Chris pushed me into a new space. This wasn’t like producing a photo-book. For the book to be successful, the photographs, culled from my personal projects across decades, needed to align with the world view that informs her writing.

CP: Bruce had a very fluid approach to the sequence of images and text, and each time I thought I knew what the book was going to be, he would come back with a new arrangement that would make my head swim: favourite images would disappear and be replaced by photos I hadn’t seen before, or change in size or place. But this turns out to be a good thing: changes up to the very last minute made the book stronger, and the process had the pleasure of a musical improvisation, or perhaps the turning of a kaleidoscope to make new patterns.

Q5: How did you two go about this? Thousands of emails? Early morning cafe meetings?

BF: We started with lunch and a beer in a sunny garden and I remember a good vibe and the beating of kererū wings. I’d already read and reread the essay numerous times. I was curious about the structure of The Lobster’s Tale. Chris explained that it was braided, comprised of fragments. I thought of the big Canterbury rivers, how the channels endlessly bifurcate and rejoin and eventually pour into the sea. I’m a big fan of essays but The Lobster’s Tale was unlike anything I’d ever read. It left me with a genuine sense of wonder: the beauty of the prose, the seamless nature of the segues between fragments, the harnessing of bizarre facts, strange coincidences and quirky observations and, finally, a profoundly moving denouement. It addresses big themes with modesty, ambiguity and sleight of hand. The lobster may be the putative subject but this piece spoke to me on so many levels. For instance, our society’s colossally inept relationship with nature, the wonderful weirdness and inventiveness of human beings, our tireless and often futile attempts as artists to express or convey meaning in our work, and the darkness that underlies so many of our thoughts. Each time I read it something else would come to the fore. It’s a most wonderful thing.

Prior to that lunch we’d joined Lloyd for the induction. He laid out the ground rules. I was relieved that he didn’t have an expectation that the photographs were to illustrate the essay. Each were to form their own narrative arc, to pick up and reflect the themes of the essay but not in a literal way. There needed to be touchstones, some points of recognition, but not in an obvious way. Lloyd and Euan’s book in this series is called High Wire, and it occurred to me that the selection of photographs would indeed be a balancing act.

CP: You could call this either a braided essay or a collage essay – both terms are bandied about in creative writing circles. ‘Braided’ fits because of the essay’s multiple strands and the metaphor of the rivers; but ‘collage’ suggests writing that develops by juxtaposition, and speaks to the visual art element.

Q6: The books in this series have a particular discipline: it all has to fit within 96 pages. Was that a struggle?

CP: Luckily the essay left plenty of room for the photographs, because shortening it would have been like pulling teeth. Each discrete section of text was always divided from the next, but the generous format of the book also allows for plenty of white space in which to sit and think before moving on. The images provide another type of interval in which to think about, and between, the meditations in the essay. The main challenge for me was writing a below-the-waterline text that would fit the number of pages available. I had to leave it fluid until quite late in the process, but from the beginning I conceived of it as a voice that had begun speaking before the book opens, and that continues speaking after it ends. Unlike me, I wrote something shorter than the word limit we’d settled on, and that meant the text came in just right. It’s in two halves, with a deliberate gap in the middle that indicates a shift in time and place.

BF: If the book didn’t have a page limit we’d still be toiling. Ninety-six pages was perfect. The process of coming up with the photo sequence was the struggle. I began by sharing images with Chris via an online scrapbook. Chris, it turned out, never does things by halves and responded to each post with a mini essay which I joyfully received and noted. I then made around 300 hundred prints and strew them round the living room in long lobster-like chains. They stayed there for several weeks before I returned to the computer and began a mock of the book, spread by spread, an intuitive response, guided by my memory of the photos and the themes of the essay and how they interacted with my preoccupations.

After another few weeks of to-ing and fro-ing with Chris, making changes, waking in the night with inspired insights and after tinkering far too much, Chris came over and we sat in front of the screen to resolve outstanding issues. As she was leaving I promised not to change a thing. Of course I couldn’t resist.

Q7: What was Lloyd’s role?

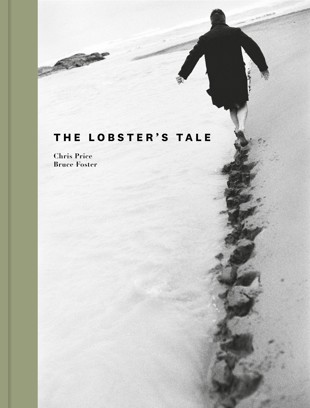

BF: A crucial meeting with Lloyd was at about the halfway point in the mock layout phase. He made a couple of particularly astute observations about what he felt was missing. The photo sequence didn’t feel anchored, he said. He proposed I establish a ‘through line’, threads of connection between images not unlike the braiding of the body text. This was achieved with the mini sequences of figures on the bridge of a ship at dusk, in which we see them alternately peering at the stars through a sextant and checking a chart. Where are we? Where are we going?, they seem to be saying. Another series is formed by footsteps in the snow that appear in two places and finally on the last page, where they come to a rather abrupt end.

CP: As far as the text goes, Lloyd’s most decisive move was actually commissioning the essay for a literary journal back in 2013. He gave me a writing prompt that went something like ‘choose an object and a word and write about it in the context of voyaging’. At that time I was embroiled in research about the nineteenth-century poet, anatomist and suicide Thomas Lovell Beddoes, who gives The Lobster’s Tale its epigraph. Beddoes’ reference to the boiling lobster had already enticed me into an exploration of its presence in literature, and the commission gave me licence to dive deep into lobster biology, ecology and beyond. Back then we talked about the possibility of making it into a book for an essay series he had in mind: I’m so grateful that idea didn’t get lost!

The second decisive intervention was asking me to add something new to the original essay. I felt reluctant to mess with the original artefact, which I’d already laboured to get the exactly way I wanted it: my solution was the below-the-waterline text, the more poetic voice that’s a continuous stream bubbling along at the bottom of the page throughout. It let me revisit the essay in the light of further developments: for instance, new ideas on things like the ‘hero’s journey’ narrative (about which the essay is sceptical, but to which it offers no real alternatives). With some help from Ursula Le Guin, the below-the-waterline text pushes back against the damaged and doomed heroes who dominate the text above. In a sense, it completes the arc between the European lobster on the book’s front endpaper and the freshwater indigenous kōura at the back: a stand-in for voices always present here, but long unheard.

Q8: The description of the way that lobsters migrate, walking in a great chain across the sea floor, is remarkable and it is but one of the many ways in which they are extraordinary. It’s hard to imagine eating one after reading this book. Has it had that effect on you?

BF: Yes, it did have an effect, not dissimilar to when I learn in more depth of the remarkable lives of some of our planet’s creatures. On the culinary side I’ve never at an interest in eating lobster. They make me violently ill.

CP: Lobsters have become my friends, even if they don’t know and don’t care. And who eats their friends?

Q9: What do you hope the readers will take from this book?

BF: I hope each reader will feel as mystified, as thoughtful and as stimulated by the texts and photographs as I do. The ‘below the waterline’ text, the single line that runs through the book at the bottom of most pages and locates the work firmly in Aotearoa New Zealand adds another level of intrigue and meaning.

I deliberately didn’t title the photos or give them locations and dates as I wanted them to be untethered from reality and available to the reader for readings that I hope will be many and various.

CP: I hope the book is an invitation for the reader to think their own thoughts, which may not be the same as mine: like a poem, it proceeds by associative leaps that leave room for the reader to make meaning. That being said, by viewing the human condition through the lens of the lobster, and through the photographer’s lens, I suppose I do secretly hope it might bolster the sense of wonder and care that is a first step towards the action of revising our human story in order to save the natural world from that narrative’s consequences – and save ourselves at the same time.

Q10: Pleased with it?

BF: I’m thrilled with everything that has gone into making the book especially my collaboration with Chris. What has also really stood out is the wider collaboration that has shaped this project and the kōrero series; with Lloyd, Nicola and Anna from Massey, and Gary, our designer from Ophir. They supported Chris and me without compromise to do the best work we could. An exceptional situation in publishing anywhere. It has been a rare and fulfilling experience.

CP: What Bruce said. What I love about Lloyd’s concept for the kōrero series is the commitment to letting the work be what it needs to be, however idiosyncratic or difficult to explain. It’s equally thrilling to find a publisher willing to back books that don’t slot neatly into any category. I love the commitment to design and production values that make for a book that is beautiful to engage with, a book that makes you want to ask the question on the Unity Books bag, ‘What’s in here?’.

And this may well be the most gorgeous book my words will ever appear in. Bruce’s poetic visual imagination makes the photos so much more than realism: more selfishly, he makes me look good! I really hope The Lobster’s Tale will find its way into the hands of all of its possible audiences: people who love literature and photography, who are curious about science, nature, history and ideas. People who love poetry too: this book is what happens when a poet writes prose.